Tuesday, December 6, 2011

Sunday, December 4, 2011

RIP Hubert Sumlin

Alas, just got the news. Here's my account of the one time I managed to see him-- with Willie Smith, also now gone.

“Music heals,” said Hubert Sumlin, between breaths. “It cures you. That’s why I’m here.”

Then he proceeded to cure us all.

Last Wednesday I went back to Jazz Alley where, a year or so ago, I saw Pinetop Perkins and Willie “Big Eyes Smith” perform. Pinetop was 97 years old at the time, bent and frail, but played and sang beautifully. (Read about it HERE.)

Last night Smith returned with a revamped band and special guest Hubert Sumlin, who brought his own special guest, Jimmy Rogers, Jr.

The night was billed as a tribute to Pinetop Perkins, but I don’t think Perkins was even mentioned. What we heard and saw, instead, was, as Mr. Sumlin pointed out, an example of the healing powers of good music.

Except for drummer “The Amazing” Jimmy Mayes, (who once worked with Jimmy Reed, and started the night with “Bright Lights, Big City,” Smith’s band was different from last year’s version. Maurice John Vaughn played guitar and could have headlined the show himself. He started with a request for “The Thrill is Gone,” and then played his own “Everything I Do (Got to be Funky).” And it was. You can read about him here. http://www.alligator.com/index.cfm?section=artists&artistid=17 Dave Kaye replaced Bob Stroger on bass. I missed Mr. Stroger’s calm smile and dapper outfit, but Kaye did a fine job.

When Willie Smith came on stage after three or four songs by the bandmembers, I was a little worried. He seemed under the weather. He is a master showman, singing, playing his harp, making people smile, but this time, at the start, he seemed to be struggling. (When Pinetop Perkins played last year, Smith was, at 74, the youth of the group.) If Smith was indeed ailing, the music didn’t hurt any for it. He sang his “Born in Arkansas,” and a song from “Joined at the Hip,” his Grammy winning album with Pinetop Perkins.

Then came Mr. Sumlin, tubes in his nostrils, oxygen tanks behind. He sat slumped on a chair. He spoke his short words about healing. He made a few tentative riffs. And then magic.

I’d never had a chance to see him play before except on video. He obviously doesn’t have the strength he once had. But he is wonderful to watch and hear. His fingers flash up and down the frets touching down to bend and slide impossibly, sometimes fingering the strings so quietly and subtly you have to watch his hands to hear, other times scratching and grating the strings to produce rough percussive sounds, usually adding a little flourish by tapping the downstream end of his strings after a lick.

They began with “Sitting on Top of the World,” which Sumlin sang. As he did so, whatever might have ailed Mr. Smith was cured, and the entire band came came alive.

From then on it was impossible to stop them. Mr. Sumlin’s anxious manager sat next to the stage and seemed to try, at least twice, to get him to quit. He kept saying “One more!” They did a song that sounded like Killin‘ Floor, but wasn’t. They did “Big Boss Man.” They did Sonny Boy II’s “Don’t Start me Talkin’.” Most of the time Sumlin seemed perfectly happy to be sitting as another sideman, keeping up a constant rhythm and providing perfect little fills, either loud and raw, or wiggly and refined. Jimmy Rogers, Jr. did beautiful solos that sounded more like a young B. B. King or Buddy Guy than his father. Maurice John Vaughn stuck primarily with rhythm but was happy to solo in his own, unique, finger picking style whenever he got the nod. Mayes kept a close watch on Smith, who led the band with quick nods. And bassist Kaye just seemed overjoyed to be there, surrounded by legends and blues journeymen, healing us all.

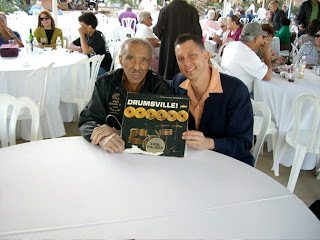

Daniel Glass and the History of Rhythm & Blues Drumming at The Drum Exchange in Seattle

Earl Palmer and Daniel Glass

|

Put on an old blues or r&b record. You always know the drums are there at the very center of it all, but sometimes it’s hard to hear exactly what the drummer is doing. (The bass drum is usually the hardest for me to find on an old record.) But that’s exactly the sound and the feel that I want-- so when I started trying to learn how to play drums I looked for some help. That’s when I learned about The Commandments of Early Rhythm and Blues Drumming by Daniel Glass and fellow drummer Zoro. It’s a goldmine, packed with drumbeats from a hundred or so r&b classics, but also packed with history-- stories and information about people like Earl Palmer and Fred Below. I’ve only skimmed the surface of what it contains, but it’s there for me.

Then yesterday Glass, a regular member of the Royal Crown Review, came to Seattle and put on a free drum clinic at a local drum store called The Drum Exchange. I took my seven year old, who likes to steal and scatter my drum sticks and knows how to do a rock beat or two. (At one point during the clinic Glass thrilled him by saying, “We all started with something like this, right?” and then played Raff’s first drum beat.) The Drum Exchange provided a beautiful room for the clinic, with a raised stage so that everyone (there had to be 50-75 people-- a full house) could see. Rafferty and I were in the first row. It was all a bit like Christmas. Glass and the Drum Exchange passed out dozens of gifts-- drumsticks, cymbals, t-shirts. Rafferty got a pair of sticks of his own, and a chart of r&b beats for his wall.

But the real gift was Glass. For more than two hours he told and played the history of drums and rhythm in America, starting with military and marching beats that got turned “ragged” deep down in Louisiana close to New Orleans. He told about the introduction of tom toms from china, bass pedals, cymbals from Turkey, high hats, smaller bass drums and ride cymbals. He put it all in the context of slavery, the gay nineties, prohibition, World War II, the swing era, be-bop, rock and roll, and finally, even a moment or two about Ringo Starr on Ed Sullivan. (If Glass saw it first hand he is remarkably well preserved.) And he did all this with incredible respect for the drummers and history that came before him. Glass is a true historian. He’s gone back and talked to them, interviewed them, listened to every beat, even played with them. (He can tell you when the first time a drummer his his crash cymbal on the "one" instead of the "four," and what recording first featured a high hat.) And he can play. That, of course, was the other treat-- when Glass would turn to his left handed drum set and play. Rafferty was squirming a bit during the lecture portions (prohibition? be-bop?) but no one squirmed during the drum exhibitions.

(Well, I take that back. I was squirming. Whenever I see someone so good I wonder why in hell’s name I even bother to head down to my basement and irritate my neighbors. As the saying goes, you can’t get there from here.)

But-- if you ever get a chance to hear Glass talk or play, take advantage.

And if you love early r&b, get his book.

As for my squirming-- it doesn’t matter. I can’t get there-- but like the duffer who once in a while hits a soaring drive-- I like trying.

Sunday, October 2, 2011

Howlin' Wolf, Chuck Berry, and $$$

Not too long ago I read a book about Howlin’ Wolf called “Moanin’ at Midnight: The Life and Times of Howlin’ Wolf” by James Segrest and Mark Hoffman. Wolf is a fascinating character—first and foremost because of his voice and his music, but also because of his contradictions. He’s said once to have chopped the top of a man’s head off with a cotton hoe; on the other hand, he’s almost universally acknowledged to be a fatherly figure and gentleman. On stage he was a wild man, crawling on all fours, dragging his “tail” to erase any tracks from his creeping; off stage, he was a quiet family man, with only occasional resort to the gun or knife.

Once, while reading B. B. King’s autobiography, I wrote about similarities between King and Chuck Berry. There were a lot of them. (Read it HERE.)

Not quite so many between Berry and Wolf—but they exist. For example, while both men are renowned entertainers, hard working and happy to mug it up on stage, both are also known to be reserved off stage.

They both were annoyed by band members drinking.

Both were professional and on time for their gigs.

Both worked continually on self improvement and continuing education. Berry used different jail terms to study business and typing and to write his book. Wolfe learned to read and write as an established star, and took mid-career classes in guitar and music theory.

Both worked at Chess Records, sharing backup musicians like Willie Dixon, Lafayette Leake, Otis Spann, and once, even Hubert Sumlin (who backed Berry on “School Day” and “Deep Feeling.”

But the most important commonality that I see has to do with money.

I’ve seen and read dozens of references about Chuck Berry and money over the years. That he insisted on cash up front. That he demanded cash. That he charged extra if a promoter provided the wrong amp. That he insisted on cash in advance during “Hail! Hail!” Some of the comments are snide—insisting that money is all he cares about.

Chuck Berry talks about money himself in “Hail! Hail” He remembers his pay at early engagements before Maybellene. He remembers how much he was paid for a paint job at The Cosmopolitan Club and then says “When the money got bigger, I put the paint brush down and picked the pick up!” He offers to sell his old Cadillacs, to YOU, for 50,000 dollars!

I remember as a young man considering with fear a statement he made in the 1960s to Ralph Gleason that he would never perform for less than $1000—and that if some “pumk promoter” offered him $950 he’d tell him “Son, you’ve just retired the great Chuck Berry.”

I had an irrational fear I would become that punk!

At least one musician in “Moanin’” said the same about Wolf. “He was mostly about money,” the musician is quoted as saying. “He conserved his money and he was always singing about money…. I don’t think I’ve ever seen him broke… He really was into that money thing and he had some money!”

But what’s important to me is that these two actually protected their own financial interests—and by extension the interests of those around them.

Wolf insisted on following the rules of the musicians’ union. Once Elmore James put his name on a poster without permission. Wolf made James pay him $25.

Wolf paid his musicians’ taxes, social security and unemployment insurance—all unheard of in the blues world of the 1950s. When he fired a musician, or there wasn’t work, that musician could still get a check. When the musician retired, he’d get a social security check.

Chuck Berry insists on getting paid up front because he knows that otherwise he might not get paid at all. He insists on union musicians. He insists on proper equipment. He shows up on time and does his job. He’s done that professionally for six decades now and as a result he is an immensely wealthy man. He owns property all over the St. Louis area.

His musicians say they are treated well—paid what they are owed, lodged at nice hotels, sometimes flown first class.

And he fought for the rights to his own songs.

In other words, Wolf and Berry, entertainers and sometimes clowns on stage, are and were serious business people, who insisted on being treated with respect, dignity and fairness in the financial rough and tumble of the music business.

It’s just another area where they deserve respect and thanks.

Once, while reading B. B. King’s autobiography, I wrote about similarities between King and Chuck Berry. There were a lot of them. (Read it HERE.)

Not quite so many between Berry and Wolf—but they exist. For example, while both men are renowned entertainers, hard working and happy to mug it up on stage, both are also known to be reserved off stage.

They both were annoyed by band members drinking.

Both were professional and on time for their gigs.

Both worked continually on self improvement and continuing education. Berry used different jail terms to study business and typing and to write his book. Wolfe learned to read and write as an established star, and took mid-career classes in guitar and music theory.

Both worked at Chess Records, sharing backup musicians like Willie Dixon, Lafayette Leake, Otis Spann, and once, even Hubert Sumlin (who backed Berry on “School Day” and “Deep Feeling.”

But the most important commonality that I see has to do with money.

I’ve seen and read dozens of references about Chuck Berry and money over the years. That he insisted on cash up front. That he demanded cash. That he charged extra if a promoter provided the wrong amp. That he insisted on cash in advance during “Hail! Hail!” Some of the comments are snide—insisting that money is all he cares about.

Chuck Berry talks about money himself in “Hail! Hail” He remembers his pay at early engagements before Maybellene. He remembers how much he was paid for a paint job at The Cosmopolitan Club and then says “When the money got bigger, I put the paint brush down and picked the pick up!” He offers to sell his old Cadillacs, to YOU, for 50,000 dollars!

I remember as a young man considering with fear a statement he made in the 1960s to Ralph Gleason that he would never perform for less than $1000—and that if some “pumk promoter” offered him $950 he’d tell him “Son, you’ve just retired the great Chuck Berry.”

I had an irrational fear I would become that punk!

At least one musician in “Moanin’” said the same about Wolf. “He was mostly about money,” the musician is quoted as saying. “He conserved his money and he was always singing about money…. I don’t think I’ve ever seen him broke… He really was into that money thing and he had some money!”

But what’s important to me is that these two actually protected their own financial interests—and by extension the interests of those around them.

Wolf insisted on following the rules of the musicians’ union. Once Elmore James put his name on a poster without permission. Wolf made James pay him $25.

Wolf paid his musicians’ taxes, social security and unemployment insurance—all unheard of in the blues world of the 1950s. When he fired a musician, or there wasn’t work, that musician could still get a check. When the musician retired, he’d get a social security check.

Chuck Berry insists on getting paid up front because he knows that otherwise he might not get paid at all. He insists on union musicians. He insists on proper equipment. He shows up on time and does his job. He’s done that professionally for six decades now and as a result he is an immensely wealthy man. He owns property all over the St. Louis area.

His musicians say they are treated well—paid what they are owed, lodged at nice hotels, sometimes flown first class.

And he fought for the rights to his own songs.

In other words, Wolf and Berry, entertainers and sometimes clowns on stage, are and were serious business people, who insisted on being treated with respect, dignity and fairness in the financial rough and tumble of the music business.

It’s just another area where they deserve respect and thanks.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)